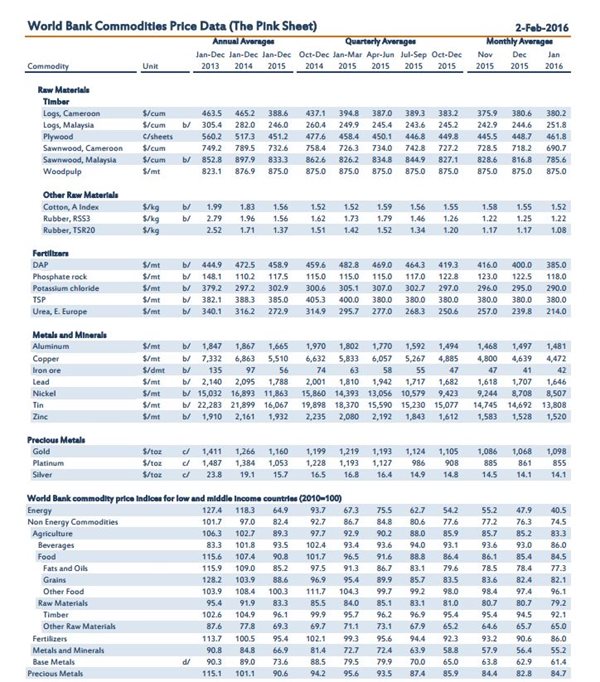

How the Oil Crisis Seeps into Commodities

The relationships aren’t simple, but one given is that energy comprises almost 50% of production costs for many commodities, including many in the agricultural sector. Cotton, for example, has the highest correlation with the crude oil of all commodities, which means it will likely be impacted, making some cotton fabric cheaper. Corn prices will likewise drop due to its lower energy costs associated with production, encouraging more planting and a higher demand for low prices, a trend that consumers can see affecting other food items as well.

For metals, the correlation is less clear-cut. Aluminum production has the highest energy-related costs; however, it also gains the least of all the metals since hydro and coal are the dominant power source for production, rather than crude oil, as well as the fact that aluminum smelters typically already have cheap electricity sources close by. It’s worth noting that metal prices were already dropping even before the decline in oil prices, which makes it difficult to gauge the nature of the relationship that exists between the two. Meanwhile, nickel producers can benefit the most from low oil prices, with the second highest fuel costs of metals, with copper producers following closely.

How the Oil Crisis Seeps into Commodities

The relationships aren’t simple, but one given is that energy comprises of almost 50% of production costs for many commodities, including many in the agricultural sector. Cotton, for example, has the highest correlation with crude oil of all commodities, which means it will likely be impacted, making some cotton fabric cheaper. Corn prices will likewise drop due to its lower energy costs associated with production, encouraging more planting and a higher demand for low prices, a trend that consumers can see affecting other food items as well.

For metals, the correlation is less clear-cut. Aluminum production has the highest energy-related costs; however, it also gains the least of all the metals since hydro and coal are the dominant power source for production, rather than crude oil, as well as the fact that aluminum smelters typically already have a cheap electricity source close by. It’s worth noting that metal prices were already dropping even before the decline in oil prices, which makes it difficult to gauge the nature of the relationship that exists between the two. Meanwhile, nickel producers can benefit the most with low oil prices, with the second highest fuel costs of metals, with copper producers following closely.

In the larger economic picture, the dip has led to higher rates of unemployment in gas-producing states such as Texas, Alaska, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, while also encouraging households to spend the money they save from lower gas prices. Though the U.S. economy is relatively diverse, and thus less dependent on the price of oil than other gas-producing nations such as Venezuela or Russia, the banking industry still takes a hit as investors who had put capital into the energy sector have to cope with their losses.

Ultimately, the low oil prices impact the U.S. in a way that does not definitively fall into a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ camp, but rather in an ambiguous manner, thanks to the diversification of industries. While the energy sector suffers during this period, conversely, other sectors where fuel costs are a dominant component of production, such as manufacturing, will see an uptick in growth.